Fasting Losing Weight Pro Ana

Materials and Methods: Thematic analysis was conducted to characterize the types of communications posted, and a content analysis was undertaken of between-platform differences.

Results: Three types of content (pro-ana, anti-ana, and pro-recovery) were posted on each platform. Overall, across both platforms, extreme pro-ana posts were in the minority compared to anti-ana and pro-recovery. Pro-ana posts (including ‘thinspiration’) were more common on Twitter than Tumblr, whereas anti-ana and pro-recovery posts were more common on Tumblr.

Conclusion: The findings have implications for future research and health care relating to the treatment and prevention of eating disorders. Developers of future interventions targeting negative pro-ana content should remain aware of the need to avoid any detrimental impact on positive online support.

Best Exercises To Lose Weight At Home

Online communities which potentially encourage eating disorders (ED) are a cause of public concern (Tong et al., 2013) and they have received heavy media attention over the last decade (e.g., Rojas, 2014). Social media has made it easier for messages which encourage or promote ED to spread; this may have negative effects on vulnerable individuals ranging from healthy individuals who may be influenced to engage in ED behaviors, through to the ‘triggering’ of individuals who may already have an ED (Brotsky and Giles, 2007; Rouleau and von Ranson, 2011; Bond, 2012). Recent research suggests a link between viewing of online ED content and offline ED behavior (Branley and Covey, 2017), although the nature of this relationship is currently unknown. Of particular concern are ‘pro’ communities that arguably aim to encourage ED behavior. For example, there are many pro-ED (also known as pro-anorexia or pro-ana) communities that construe ED as a lifestyle choice rather than disorders to be treated (Wilson et al., 2006; Bond, 2012; Syed-Abdul et al., 2013; Tong et al., 2013). By encouraging each other to engage in associated ED behaviors, pro-communities normalize the behavior by making the user feel that it is acceptable, justifiable, and sometimes even desirable (Schroeder, 2010). Similarly, media portrayal of celebrities with perceived ED has been liked to an online practices around ED (Yom-Tov and Boyd, 2014). Another concern is the potential for pro-communities to glorify or romanticize ED, for example by portraying the behaviors as ‘tragically beautiful’ (Bine, 2013). Concerns are heightened further due to the interactivity of social media, (Borzekowski et al., 2010) and its heavy use by young users – the age group most affected by ED (Arcelus et al., 2011).

These concerns generally result in a call for interventions based upon censorship, i.e., removal of ED content from the platform (Tong et al., 2013) or warning messages or warning messages (online alerts displayed to users explaining that content associated with ED keywords or search terms can have the potential to be upsetting and/or triggering). However, these generic messages appear regardless of the type of ED content actually being returned by the search and users have to bypass this message even if searching for positive content (e.g., seeking information regarding recovery). This could render the warning meaningless. Censorship of ED content could also backfire; social media use has been linked to mental health wellness through contribution to perceived social support (Asbury and Hall, 2013) and not all online communities encourage ‘pro’ attitudes toward ED. Many feature information on recovery and some communities are supportive of users who decide to seek treatment (Brotsky and Giles, 2007; Csipke and Horne, 2007; Lipczynska, 2007). Therefore it is possible that social media provides a platform through which users can find help and guidance – this is particularly important as ED sufferers rarely seek professional help (Cachelin and Striegel-Moore, 2006). If there are positive elements to social media, then censoring content without any regard for the impact of the loss of positive social connections could have a negative effect upon users’ wellbeing.

It is important therefore that we truly understand the nature of online communities before introducing interventions. In particular, we need to know more about the types of ED-related information people using social media are being exposed to. However, our understanding is limited because previous researchers investigating online ED content have tended to focus upon pro-ED content and not ED-related content more generally (Norris et al., 2006; Brotsky and Giles, 2007; Lipczynska, 2007; Tong et al., 2013). The current study addresses this limitation by analyzing the full range of ED-related content shared by social media users. With no restrictions this analysis provides a balanced insight into the different ways in which ED is portrayed on social media. Focus is placed upon comparing the content on two popular social media platforms that have been linked to disordered eating behaviors in the press, Twitter, and Tumblr (e.g., “Becoming what you don’t eat” [Twitter], The Daily Iowan, June 26, 2014, “The hunger blogs: A secret world of teenage thinspiration” [Tumblr], Huffington Post, September 2, 2012). Whilst Twitter and Tumblr are both blogging platforms they differ in their functionality and the environment they create for users therefore allowing us to investigate whether the environment that is provided by the platform may impact upon the type of content shared by users. For example, users often perceive Tumblr as more private in comparison to Twitter therefore it is possible that this may influence the type or severity of the content shared (Marwick and Boyd, 2010).

You Don't Look Anorexic'

The research was reviewed and approved by the Durham University Institutional Review Board. Data was collected from Twitter and Tumblr from a 24-h period on June 12, 2014 providing a comparative analysis of ‘one day in the life’ of ED-related posts on the two platforms. The date was selected randomly from all dates within a 3 month period in 2014 (May to July). However, to ensure that the selected day was representative of a normal or typical day, dates within 2 days of a recognized holiday were not included in the selection particularly as religious holidays might impact upon eating behavior.

Due to public API’s imposing limitations on the data that they can provide (Morstatter et al., 2013; González-Bailón et al., 2014), the Firehose was used to access the Twitter and Tumblr data. The Firehose provides full, unlimited access to the complete database of publicly available data on the platforms. Access to the Firehose was obtained using Topsy (Twitter data) and DiscoverText (GNIP Firehose for Tumblr data).

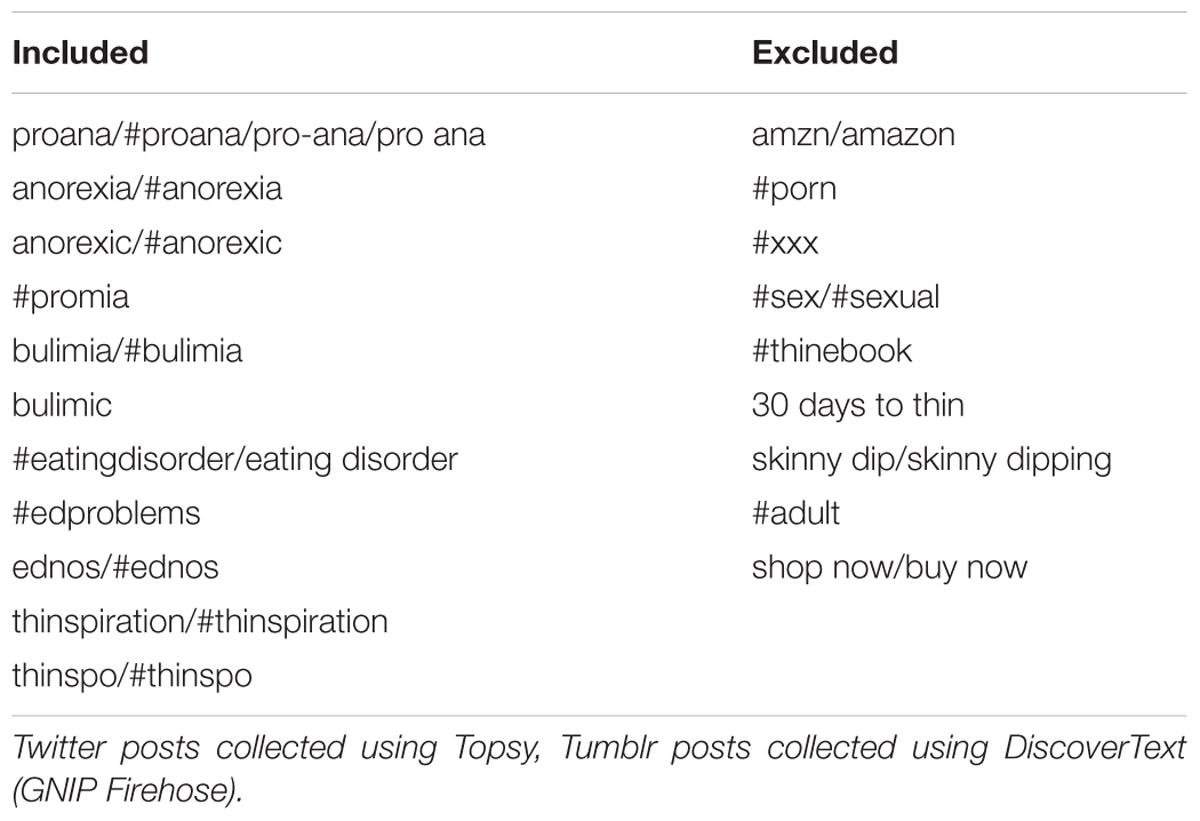

The website www.hashtagify.me was used to identify the 10 most commonly used hashtags (#) relating to each of the following ED terms: anorexia, ED, proana, pro-ana, pro-ed, and proed. Although hashtagify.me is a Twitter specific search engine, it can still be useful when trying to identify search terms in general – at least in the initial planning stages. Using the list of terms gathered using this technique, the researcher DB manually searched for each of these terms on both the Twitter and Tumblr platforms and noted any other ED-specific terms which had not been captured. This produced a list of 55 potential search terms. In order to narrow this down to the most relevant search terms, each of the terms were entered into Topsy which provided an estimate of the daily number of tweets. Any terms showing a frequency of less than 100 tweets per fortnight were excluded from the list of terms used for data collection shown in Table 1.

A Twisted Comparison Game': How Fitness Apps Exacerbate Eating Disorders

The searches conducted using the terms shown in Table 1 produced a database of over 12, 000 tweets and 73, 000 tumblogs. An inductive, thematic approach to the analysis was adopted to identify patterns or themes within the posts (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Joffe, 2011). This approach has the ability to identify manifest and latent motivations that drive behavior (Joffe, 2011); therefore helping to achieve the goal of understanding ED communities from the perspective of the users (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Posts were randomly selected from each database until data saturation was reached and no new themes were obtained. Posts that were clearly spam or not written in English were excluded from the analysis.

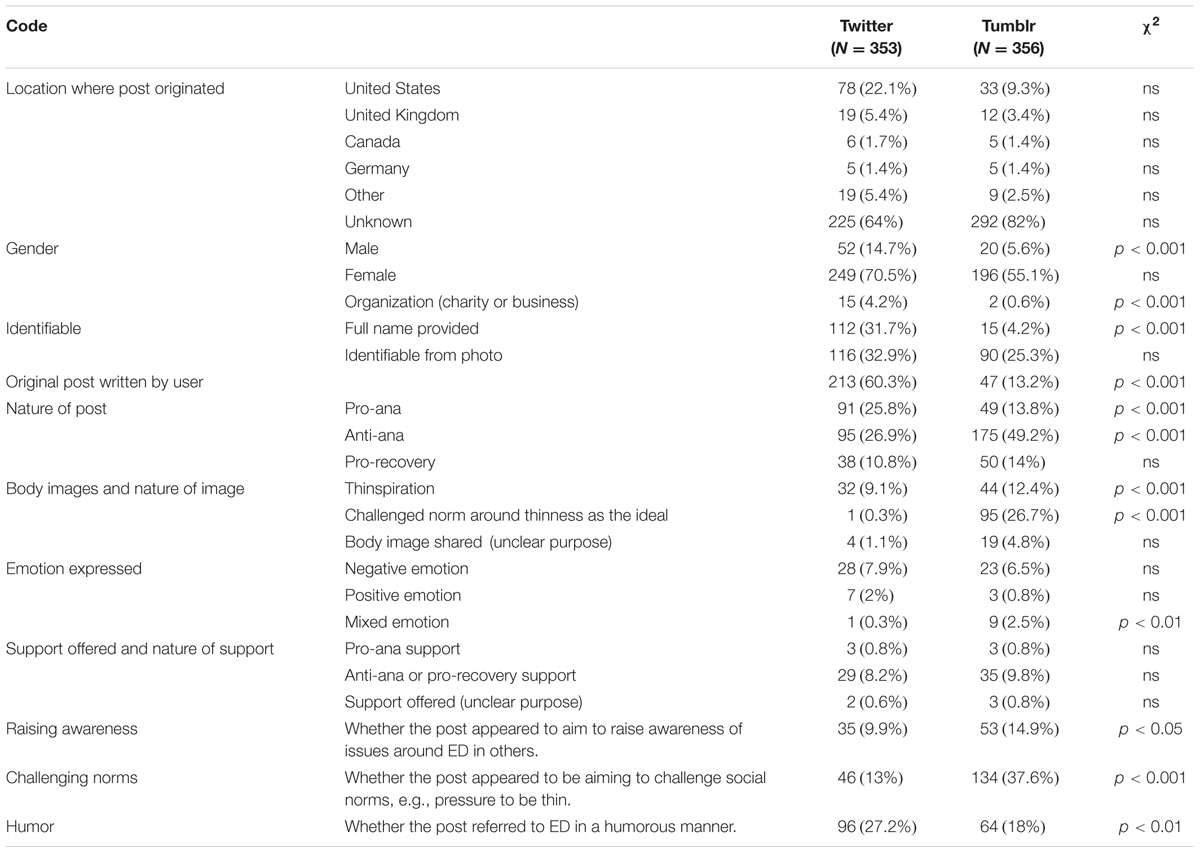

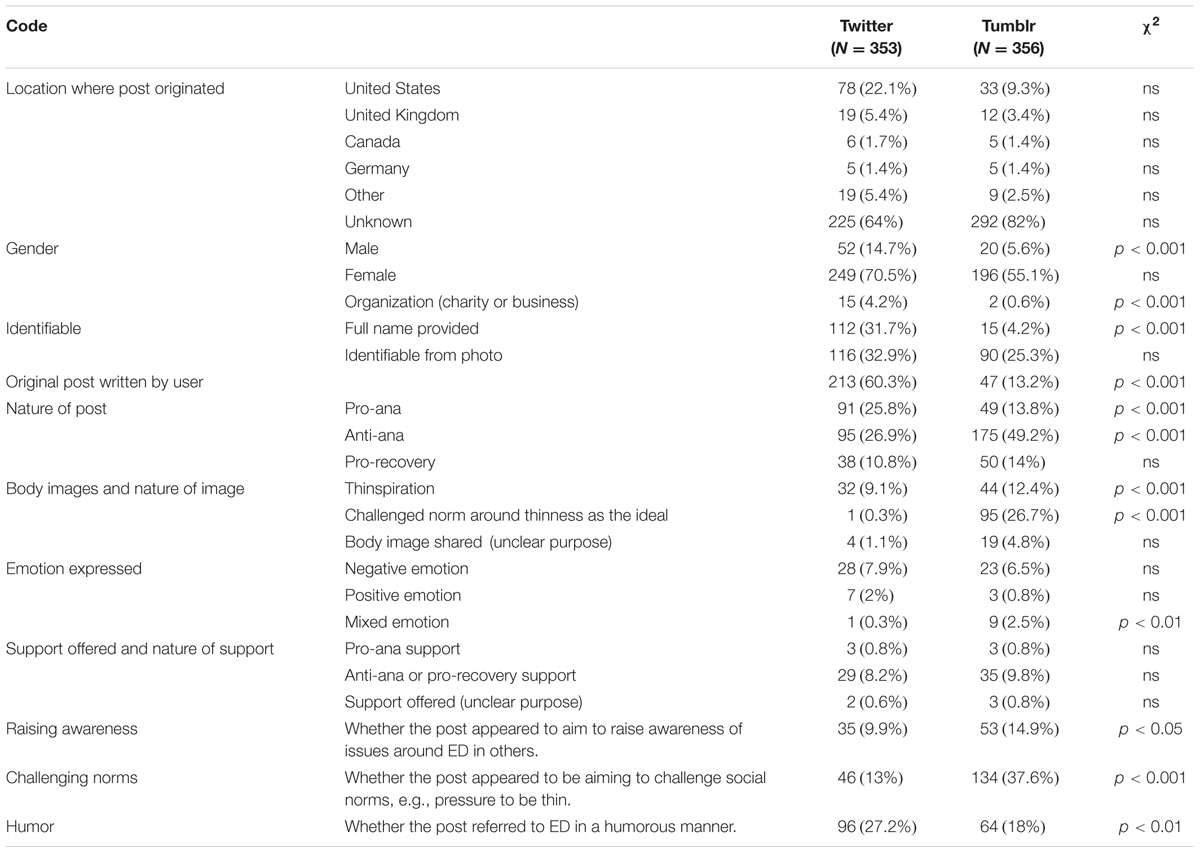

The themes identified from the thematic analysis were used to develop the coding scheme for content analysis. The coding scheme was tested for inter-rater reliability on a randomly selected subsample of 80 posts. The coding scheme was refined and repeatedly tested on new subsamples of posts until all codes had a Kappa value greater than 0.70. The final coding scheme is shown in Table 2. The content analysis was then conducted on a new random sample. The aim of this analysis was to compare the content between the platforms; power analysis confirmed that a sample of 350 posts from each platform was sufficient to detect a small effect size using Chi-square tests (power = 0.80, α = 0.05, φ = 0.12).

One hundred and ninety posts were sampled to reach data saturation in the thematic analysis. In order to ensure user anonymity no user IDs, names or profile photos are included in the results. Also, any posts referred to in the results are paraphrased to prevent possible user identification.

I Spent A Week Undercover In A Pro Anorexia Whatsapp Group

Three distinct types of posts were identified from the thematic analysis: pro-ana, anti-ana, and pro-recovery. For the purpose of this research and in keeping with the context in which the

The searches conducted using the terms shown in Table 1 produced a database of over 12, 000 tweets and 73, 000 tumblogs. An inductive, thematic approach to the analysis was adopted to identify patterns or themes within the posts (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Joffe, 2011). This approach has the ability to identify manifest and latent motivations that drive behavior (Joffe, 2011); therefore helping to achieve the goal of understanding ED communities from the perspective of the users (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Posts were randomly selected from each database until data saturation was reached and no new themes were obtained. Posts that were clearly spam or not written in English were excluded from the analysis.

The themes identified from the thematic analysis were used to develop the coding scheme for content analysis. The coding scheme was tested for inter-rater reliability on a randomly selected subsample of 80 posts. The coding scheme was refined and repeatedly tested on new subsamples of posts until all codes had a Kappa value greater than 0.70. The final coding scheme is shown in Table 2. The content analysis was then conducted on a new random sample. The aim of this analysis was to compare the content between the platforms; power analysis confirmed that a sample of 350 posts from each platform was sufficient to detect a small effect size using Chi-square tests (power = 0.80, α = 0.05, φ = 0.12).

One hundred and ninety posts were sampled to reach data saturation in the thematic analysis. In order to ensure user anonymity no user IDs, names or profile photos are included in the results. Also, any posts referred to in the results are paraphrased to prevent possible user identification.

I Spent A Week Undercover In A Pro Anorexia Whatsapp Group

Three distinct types of posts were identified from the thematic analysis: pro-ana, anti-ana, and pro-recovery. For the purpose of this research and in keeping with the context in which the

Post a Comment